EQ118.16. It is the USEF rule that every equitation rider has imagined but few have experienced – the exchange of horses test, where riders are asked to dismount from their own horse and climb aboard the mount of their competitor.

EQ118.16. It is the USEF rule that every equitation rider has imagined but few have experienced – the exchange of horses test, where riders are asked to dismount from their own horse and climb aboard the mount of their competitor.

Most equitation riders go an entire career without being asked to perform this unique test, individual pattern work being the much more common course of events, and this is no surprise since the test has always been at least slightly controversial. Top show horses cost a lot of money; what happens if one pulls a shoe or injures itself with another rider on board? What about the liability? And, perhaps the biggest question of all: does it really prove what is intended?

But despite all of these concerns, the test has prevailed. Today, due to its controversy, it is used rarely and only as a tiebreaker, yet it remains a longed-for addition to equitation competition, known for prompting some of the greatest moments in the sport’s history, and providing new thrills to an industry desperate for excitement.

The exchange of horses test has been in effect for decades, with minor changes throughout the years. The current rule reads: “Exchange horses. This test is to be used only after four or more of the top riders have been tested. Only one pair of riders to exchange. Saddles can be exchanged. The attendant for each horse being exchanged must be allowed in the ring only to facilitate the change. The purpose of this test is to break a tie.”

Knollwood Farm trainer Scott Matton was chair of the UPHA Equitation Committee and a member of the United States Equestrian Federation Saddle Seat Equitation Committee when this version of the rule was put into effect in 2001.

“It needed to be revised because it had been so abused,” Scott said. “There were no guidelines. They were doing it just for the sake of doing it and watching the inequality that had happened.”

Before the 2001 rule change the exchange horses test was sometimes used as the sole workout for a class, and that caused problems with the exhibitors who felt another test, such as a pattern, would have better displayed their skills. Since only a small number of riders were asked to switch horses, it also had the potential to leave the majority of riders being judged on nothing but rail work. In the interest of fairness, the current version of the rule made it clear that horses were to be exchanged only after at least four riders had been tested in some other manner – a good thing, since it also further limited how many riders were allowed to exchange, narrowing the number from three to just two.

With this change the test became a straight up swap rather than an “everyone move to the horse to your left” sort of event. Limiting the rule to a tiebreaker scenario between two riders thought to be of equal ability was intended to do more than make the test fairer, it was meant to make it safer – an important consideration, as accidents do happen, and they may not even be the rider’s fault.

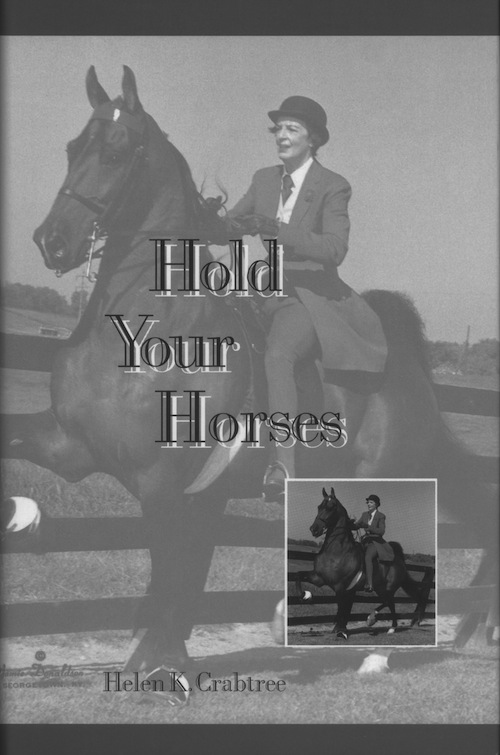

In her 1997 memoir, “Hold Your Horses,” equitation legend Helen Crabtree wrote about one such event during the 1979 AHSA Medal Finals, where, after a long and grueling class and workout, her student, Shauna Schoonmaker, was asked to switch horses with competitor Ashley Tway, coached by Harold Adams. Shauna switched from the great Glenview’s Warlock to Ashley’s dainty mare to find that the horse was so tired her shoulder muscles and front legs were shuddering. Though the mare did her best, she fell to her knees during the second way canter, and Shauna performed some of her best riding when she threw her weight back in the saddle and literally hauled the horse back to her feet. Ashley was tied first in the class, and even Helen noted that she deserved the win. But if the misstep of a tired horse was the deciding factor, did that mean that Shauna’s ability was any less? It is grey areas like this that cause reservations about the test, even when the exchange is limited to just two riders; if it relies so much on luck, what exactly does it prove?

Scott’s wife, Carol Matton, believes this question applies to a much broader range of scenarios than just switching to a fatigued horse.

“Some horses have serious tricks to them and you can't always figure that out on the fly,” Carol said. “On the other side of that coin, that’s what it was intended for. It’s kind of a two-edged sword.”

If both horses are equally tricky, it’s not really a problem. But it is when the horses offer very different levels of difficulty that the test’s value is called into question.

“If you have an easy horse, anybody can ride that,” Scott said. “If you've got a horse that took your kid a year to learn to ride, that's not fair, either.”

In other words, riding an easy horse well doesn’t prove that a rider is exceptionally skilled, and putting in an average or poor ride on an extremely difficult horse doesn’t prove that a rider isn’t.

There are a myriad of other concerns heard throughout the industry as well. A parent may not be pleased to watch someone else’s child beat his own aboard the horse he purchased at great expense. Additionally, switching riders around disturbs the picture that trainers and instructors have carefully worked to cultivate.

“That's my combination,” Scott said. “If I’ve got this tall horse for my kid and they end up putting her on a walk trot pony how does that make her look?”

Lillian Shively of DeLovely Farm has perhaps had more of her students perform the exchange horses test than any other instructor today, and, like Scott and Carol, her views on the test lie somewhere in the middle.

“There are holes in everything,” Lillian said. “I prefer to think there are no holes in anything that can't be worked through.”

In this spirit she believes the test can be of value when used properly, but she also believes there are many times when it should be avoided.

“I feel strongly that you shouldn’t be doing it to be grandstanding,” Lillian said.

When it comes to concerns of safety and liability, Lillian puts her trust in the other industry professionals.

“Most of these horses are trained by people who are so knowledgeable,” Lillian said. “They’re not going to put their child on something that's going to fall over backwards. Most everybody is covered liability-wise anyway.”

Of course, she hasn’t had to think about liability too much; when the test has been called for in the past, her riders have often been asked to switch with each other. This was exactly what happened in the 1992 AHSA Medal Finals when her student Emily Swanson was asked to switch horses with her fellow barn mate and best friend.

“It was always one of those things you thought could happen but never really thought would,” Emily said, looking back on the event more than 20 years later. “I’d never even watched it except on videotape.”

There was no workout during Phase 2 that year – something that would be banned under today’s rule – but there was little doubt that the exchange made sense. Both horses and riders had very different styles, and each horse, though safe, presented challenges that forced the riders outside their comfort zones.

“Some riders are really aggressive and some are really elegant, and if they match their horses that works really well, but what happens when you swap the styles?” Emily asked.

What happened in their case was a demonstration of real horsemanship, with two great riders giving it their all on their new mounts. It was also a grand display of sportsmanship; Emily handed her spurs to her friend, who she knew would need them more, and, though Emily won the class, the two girls took the victory pass together.

A similar instance took place in the 2009 USEF Medal Finals with another pair of Lillian’s riders, Faye Wuesthofen and Ellen Medley Wright. In an interesting twist, Ellen’s mount was sick, so she came into the ring already riding a borrowed horse, barn mate Brittany McGinnis’s gelding Soli Deo Glori or “Jack.” Faye began the class riding her own CH-EQ Kiss Of The Zodiac, or “Zodi.”

Both girls put in fantastic rail work and patterns, making it almost impossible for the judges to decide between them.

“On that given day it was a dead heat,” Lillian said. “I'm not so sure, if I'd been judging, I would've known what to do.”

When the judges called for the exchange of horses, Kemper Arena exploded in excitement.

“Ellen so impressed everybody with what she was able to accomplish that day, with her ability to go in there and ride the pattern,” Lillian said. “Because of that I think they needed to see if, indeed, Faye was the outstanding superstar that everybody felt she was.”

Of course, Lillian knew better than anyone that this was true. “She had an amazing feel for a horse,” she said. “There was nothing man-made or instructor-made about her.”

As expected, Faye rode Jack as if she had been riding him forever. Ellen, however, ran into a little more trouble; Zodi had a complicated and touchy mouth, and Ellen had caught him on a particularly bad day.

“Zodi wasn't wanting to wear his bridle that well that day anyway,” Lillian said. “And when he said ‘enough of you’ he said ‘enough of you’ and that’s the way it was, so he kind of raised up with her.”

In the end, Faye was named the winner, clinching the Equitation Triple Crown in the process. Few will argue with the results of that class, but it solidified the fact that there is an element of luck to every horse exchange, even with horses as great as Jack and Zodi.

But that is the nature of EQ118.16, even when used correctly: it always shows whether a rider can apply their skills to an unfamiliar horse, but only sometimes shows whether or not they can do so better than their competition. It is, therefore, up to each individual to decide whether or not it’s worth it.

As for Lillian, the memory of the crowd’s reaction to Faye and Ellen’s 2009 horse exchange makes her decision a little easier.

“I will say this,” she said. “Everybody stayed in their seats. Nobody got up. Nobody left. And the crowd went wild.”