Have you ever known a horse that performed well at home but whose behavior changed negatively at a show? What about a horse that lollygagged through its work sessions at home but suddenly became all show horse when trotting through the in-gate? Horses that perform one way at home or in practice often have a change in behavior and performance when competing at a show, and there may be a variety of reasons for this change.

Have you ever known a horse that performed well at home but whose behavior changed negatively at a show? What about a horse that lollygagged through its work sessions at home but suddenly became all show horse when trotting through the in-gate? Horses that perform one way at home or in practice often have a change in behavior and performance when competing at a show, and there may be a variety of reasons for this change.

According to Tom Thorpe, trainer at Northern Tradition Farm in Minooka, Illinois, change in environment is a key factor. At home everyone is comfortable and the horse is familiar with what goes on. At the show it’s not just the show ring but the transport, stabling, the warm-up, other horses – everything is different.

“This doesn’t include all the things you can’t plan for, like strange noises, or other horses’ behavior in the ring,” Tom said. “They feed off one another. If a horse is ill-mannered in the ring or extremely nervous, it throws everything into a tizzy.”

Behavior is a Complex Response to Environment

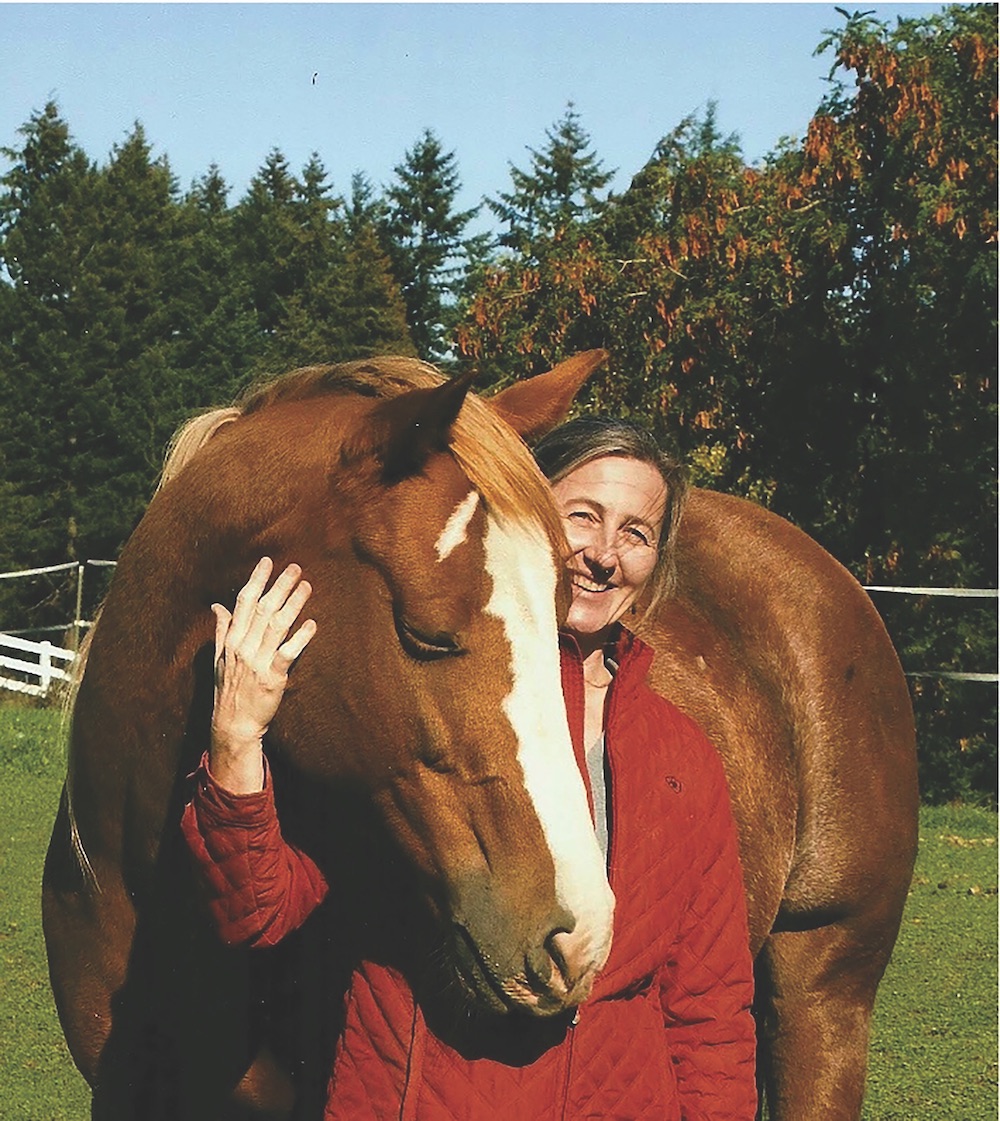

Dr. Robin Foster, a certified Applied Animal Behaviorist and Horse Behavior Consultant – and Professor at University of Puget Sound and University of Washington – agrees that environment plays a huge role in a horse’s behavior.

“Behavior happens within a context and in some cases specific to that context,” Foster said.

What a horse does in one context doesn’t mean this is what he’ll do in a different context. Horses are sensitive and react to their environment, paying attention to everything around them.

Distractions can affect a horse’s attention to the rider.

“You won’t get expected performance because the horse is not focused on the task at hand,” Foster said. “Context can also affect motivation – whether the horse listens to the rider or is trying to get out of there. It affects level of arousal and emotional state, which affects behavior, in a positive way or a negative way.”

Location is part of the context.

Location is part of the context.

“Is the horse in an unfamiliar place? How many people are there? Is the spectator audience loud or quiet? How many other horses are nearby, and what are they doing? How close are they? Presence of unfamiliar horses seems very stressful for some horses,” Foster said.

The performance of horses trained beforehand for this kind of environment will be less affected by it.

“If the training situation is very different, we can’t predict that the horse will perform the same way in competition as he did during training,” she said.

Riders might try to pinpoint which features of the environment are most troubling – the noise, the transport, waiting around, or the whole package? Every horse is different, and there might be differences in the horse’s experience from one show to another. In one situation the horse is first to show, and two weeks later the class is mid-day in the heat, with a lot of waiting around.

During training it’s the same barn, same arena, same people, same horses and same routine. It’s best to train in progressive steps, if possible, introducing the horse to a show environment before actually going there to compete.

“So much is unplanned and uncontrolled,” Tom said. “It’s hard to be prepared for everything. I’ve never figured out a way to replicate a show setting at home. You can use other horses, but it’s not different enough.”

He recommends hauling horses to shows before they actually show, to let them experience the change in environment.

“Many come back with a better mind frame; it helps them fill in blanks in their training,” he said. “It may have rattled their cage a little, in that environment, but they come home and are more comfortable and take to the training so much better.”

It’s a step forward, having that extra experience. They realize they survived it, and it’s no big deal.

“We like to do this with our young horses, or any horse that hasn’t shown for a while, as a refresher to get them off the farm before we throw that extra pressure on them,” Tom said. “They usually don’t mind, and many actually thrive on it; it gets them ramped up because they want to go.”

Adrenaline can be Useful

While some horses may do fine in practice and not-so-great during competition, sometimes the opposite is true. Some horses may not put their heart and effort into a practice workout and then during competition are more engaged and on their toes, at the top of their game.

A little pressure/excitement can stimulate them to be more alert, with adrenaline going, to bring out their best performance.

“With Saddlebreds, we want them excited and energetic,” Tom said.

You want to get them to that point but not beyond – with too much excitement for them to handle.

“Dick Durant always said that horses never win classes in their stalls,” Tom said. “They need some adrenaline going, as long as you can harness it correctly.”

Dick Durant was a well-known and respected Saddlebred horse trainer from Bell View Acres in Lemont, Illinois.

“That’s the big trick, and it goes back to just practicing once – in a kind of dress rehearsal at a show,” Tom said. “This helps the horses know that what we do day in and day out makes sense, and we also find out whether we are prepping them correctly.”

Some horses are completely different in the show ring. There are so many extra things to look at, and this can either help or hurt their performance. Every horse is different and you have to feel your way.

Some horses are completely different in the show ring. There are so many extra things to look at, and this can either help or hurt their performance. Every horse is different and you have to feel your way.

“With some horses, just the crowd and noise really upsets them, whereas others feed on that excitement and just move bigger and better,” Tom said. “If they give a great performance and there’s not that crowd support, they are kind of taken aback, like, ‘Wait, I thought I was doing it right. Where are my accolades?’ When you get a horse like that – one that seems to understand that the crowd is clapping for them – they are fun to show.”

Yerkes-Dodson Law

Foster said that a horse’s response to a show environment can be explained by the Yerkes-Dodson law, which applies to animals as well as humans. This is an observed relationship between arousal and performance, originally stated by psychologists Robert M. Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson in 1908, which says that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a point. Physiologic arousal due to stress/anxiety (resulting in increased heart rate, etc.) at certain levels can enhance performance, but too much arousal can hinder it.

At one extreme is too little arousal; the horse is totally relaxed and you can hardly get his attention, like the old school horse that ignores the rider’s cues, and performance is terrible.

“The Yerkes-Dodson curve is an inverted U or bell curve; as physiological arousal increases, the horse pays more attention,” Foster said. “Heart rate is elevated a little and he’s breathing a little deeper, sending blood and oxygen to skeletal muscles, and he gives a great performance. This is where you want him, in that sweet spot for performance.”

Once a horse gets past that spot and becomes over-aroused, you lose his attention again, and performance suffers. He’s too nervous and distracted, in a flight response.