The idea

It all began around four-thirty on a Friday shortly after the start of the university’s fall semester. Though Schiltz had been treating the William Woods horses for 18 years as a primary care veterinarian, it was his first semester as staff veterinarian, and he had joined Pullen in his office to discuss an equine lameness therapy known as Platelet-Rich Plasma, or PRP. As the two men discussed the therapy and their backgrounds, Pullen mentioned his work in stem cell research.

It all began around four-thirty on a Friday shortly after the start of the university’s fall semester. Though Schiltz had been treating the William Woods horses for 18 years as a primary care veterinarian, it was his first semester as staff veterinarian, and he had joined Pullen in his office to discuss an equine lameness therapy known as Platelet-Rich Plasma, or PRP. As the two men discussed the therapy and their backgrounds, Pullen mentioned his work in stem cell research.

“My background is actually human biomedical,” Pullen said. “My work in allergy and asthma research involved a lot of work with the bone marrow of mice and people.”

Since the mice were killed to extract the bone marrow, and people put under anesthesia, Pullen had always assumed performing the procedure on an animal as large as a horse would be next to impossible. He was shocked when Schiltz told him that not only could he get horse bone marrow quite easily, he had already done so a number of times in private practice, collecting the bone marrow and sending it to a commercial company that would package it for injection. As they continued their discussion, a daring question began to emerge: what if they could replicate this procedure on campus, treating their horses without the need for a commercial company, and using it to drive creative and scholarship experience among their students at the same time?

As it turned out, Pullen already had a particular student in mind for the project, senior Joanie Ryan. A dressage rider and biology major with a minor in equestrian science, she had worked with Pullen on his cancer research for two years and even had some experience collecting equine bone marrow.

“When I was thinking of going to vet school I worked for a clinician in Colorado in the summers, where I was first introduced to different lameness therapies,” Ryan said. “There we collected bone marrow from the hips.”

When Pullen approached her about the project she was excited, but not surprised.

“He said, ‘did you know we can get horse bone marrow?’ And I said, ‘yes it's really easy,’” Ryan said.

The process

It was decided that Schiltz would collect the bone marrow from university-owned horses and provide it to the biology department, where Pullen and his students would work to extract and grow the stem cells, and eventually package them for injection back into the horse.

It was decided that Schiltz would collect the bone marrow from university-owned horses and provide it to the biology department, where Pullen and his students would work to extract and grow the stem cells, and eventually package them for injection back into the horse.

“The process begins with a bone marrow aspiration,” Schiltz said. “We clip and surgically prep a spot on the horse’s chest and use an ultrasound to locate the segment of the sternum that we are going to aspirate the bone marrow from. You actually have to drill the needle through the bone and then into the marrow cavity before you start aspirating, drawing the bone marrow out into a syringe that contains a drug called Heparin that keeps it from clotting as bad.”

While the procedure sounds extreme, the horses actually tolerate it very well, and have almost no residual effects.

“I had previously done the first part of the procedure in private practice, but when it was over the horses would go home, so when I first did it here I was a little uncertain as to what to expect in terms of aftercare,” Schiltz said. “But the next day there was never any indication the horse had the procedure done. All they need is a few days of stall rest, hand walking and a topical antibiotic.”

After the aspiration, the syringe containing the bone marrow is capped and handed off to Pullen. At the first draw, Pullen was surprised that it contained 40 ccs.

“Working with mice and people I was used to maybe getting two percent of that,” he said.

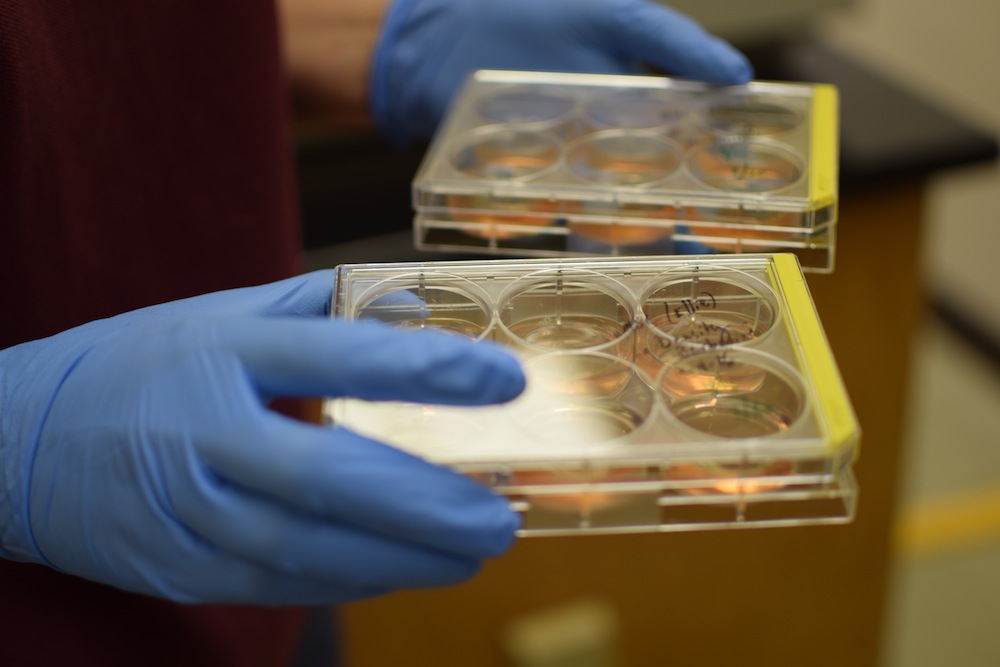

Next the sample is taken to the university’s biology lab, where it undergoes some intense manipulation.

“We take the bone marrow and process it through some filters to isolate the cells,” Pullen said. “Then we grow them in this liquid culture medium that has all these other factors in it idealized for stem cells,” Pullen said.

They tested three different protocols for isolating the stem cells. While all the methods worked to some degree, it quickly became clear that one particular method worked best.

“It's a lot cleaner with this method,” Pullen said. “You're isolating fewer cells and encouraging them to grow.”

Of course, this method also seemed to take significantly longer than the others, such as the method used by commercial companies.

“The protocol that works the best takes four to six hours to set up,” Pullen said. “In comparison, the commercial one takes twenty minutes.”

It took longer to be sure of the results, too.

“With the method that seems to work best, it seems to take at least three weeks until you're confident it’s not contaminated with something else,” Pullen said.

Though Schiltz, Pullen and Ryan all had significant experience with bone marrow or stem cells, none of them had worked specifically with horse stem cells, and that was the biggest challenge.

“We were just learning how they grow and keeping it clean,” Ryan said.

But the challenge was worth it with the end goal in mind – returning the stem cells back to the horse.

The reward

Though stem cells can be used to treat any injured tissue, in performance horses this usually involves joint injuries, or soft tissue injuries such as torn ligaments and bowed tendons, all familiar problems in the William Woods stable.

Though stem cells can be used to treat any injured tissue, in performance horses this usually involves joint injuries, or soft tissue injuries such as torn ligaments and bowed tendons, all familiar problems in the William Woods stable.

“The ultimate reward is having the ability to clinically treat the horses,” Schiltz said. “The treatment is available commercially, but is extremely expensive. For that reason alone it's not been an option for the William Woods horses until now.”

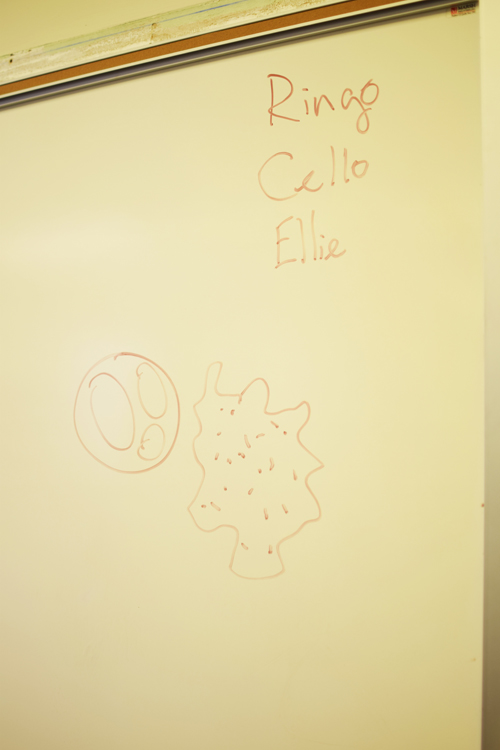

While the first two aspirations Schiltz performed at William Woods were not clinical cases, the third one was performed on an Arabian mare from the western string known as L E Gant, or “Ellie,” who had fractured her right front elbow.

“It’s not a large fracture, but it is in a location that we can't access it surgically,” Schiltz said. “We hope that by providing stem cells to the fracture site we can have it differentiate into cartilage cells.”

Of the three aspirations Schiltz performed, Ellie’s case was the most difficult and provided the least amount of bone marrow.

“It took a while to get it growing,” Pullen said. “They're kind of funny little things. When you have a situation where you don't start with many you can get really down because it looks like nothing is happening and then within a period of twenty-four to forty-eight hours they start to grow.”

Currently Schiltz and Pullen are only utilizing bone marrow from the same horse they are trying to treat; they are not attempting to treat horses with stem cells taken from the bone marrow of a different horse.

“There is work being done on that, but not here,” Schiltz said.

Education

“It's afforded a lot of opportunities, and obviously from an educational standpoint that’s the best thing,” Schiltz said.

Students were involved in the entire process, testing growth protocols and examining different bone marrow aspiration techniques. Pullen’s biochemistry class studied the different molecular markers of mesenchymal stem cells, or MSCs, and Pullen himself received an education in all things equine.

“I figured working at William Woods I would eventually have some interaction with the horses,” Pullen said. “Half of my students do ride.”

But of all the people who have benefitted from the research, Ryan may be the one who has gained the most, learning about lab techniques, primary literature searches and more. She and Pullen have even received a grant from the American Association of Immunologists to pay for their participation in the Immunology 2016 conference in Seattle, where she will be presenting the results of their research. After graduation this spring she plans to attend graduate school, and hopes to eventually put her knowledge to good use working for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It has been an incredible experience for an undergraduate student, and Ryan is entirely aware of this fact.

“You're not going to hear of another place that allows students to do this,” she said.

It is the best kind of collaboration – the kind where everybody wins.